Searching for the Dark

The Bortle Scale

A device for measuring the weight of Bortles?

Buzzzzt! No, I’m sorry. That is incorrect.

“The Bortle scale is a nine-level numeric scale that measures the night sky’s brightness of a particular location.”

The scale was proposed by John E. Bortle in Sky & Telescope magazine in 2001 as a standard measure to quantify light conditions across astronomy observing sites. It caught on as Necessity’s Mother.

Class 1 sites present the darkest skies on Earth. If that is where you are, stay put; it doesn’t get any better anywhere else. On the other hand, light pollution at a Class 9 site obscures everything but the Moon, the brightest planets, and the expanding swarm of Elon Musk’s minions. It is thin gruel.

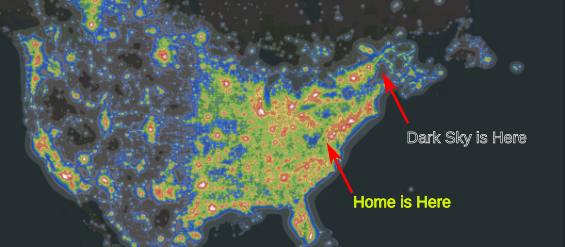

Where I live, the Bortle Scale rating is 4.5, which means that light domes from nearby humanity wash out most stars located below about 45 degrees above the horizon. On a dark night I can begin to imagine the Milky Way directly overhead. But I am sure I am not sure.

.=.=.=.=.=.=.

The night was clear and crisp. I stared out the passenger-side window of the old yellow Ford station wagon. Off to visit Grandma and Grandpa on the farm in East Aurora. A long drive on dark country roads. I could see more stars, it seemed, than grains of sand on the Sea Breeze beach. Orion rose in pursuit. The reality of it more profound, for this eight year old, than if gods had painted the stars on a dome in the sky, and what could be more profound than that.

Bortle hadn’t yet invented his eponymous scale in 1956. Light pollution hadn’t weaseled its way into the landscape yet either. Everywhere, but maybe New York City, eh, was Class 1, wasn’t it? Unfortunately, bright lights had other imperatives, and their intrusions expanded steadily over the decades without eliciting much notice, until here we are.

It is now a long way from home to the nearest Class 1 dark sky; 877 miles to be exact. In the continental US, there is but a single Bortle Class 1 dark sky site remaining east of the Mississippi river. Deep in the Maine Woods.

.=.=.=.=.=.=.

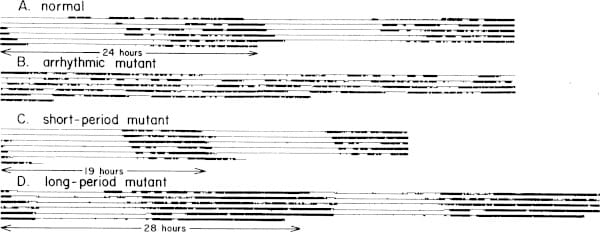

Fruit flies, bless their little bug-eyed selves, work all day and sleep all night. You can measure it. Ron Konopka and Seymour Benzer did exactly that back in the late 1960s. Time the movements of Joe Random Fly in the lab and you generate traces like the ones shown in the top panel of the figure below (A. normal). (Here the x-axis is time, proceeding left to right; black traces mark periods of fly movement.) What you discover with this exercise is that Joe Random Fly break dances for about 12 hours and sleeps it off for about another 12 hours. A 24 hour cycle. Over and over. As sure as day follows night.

Being the mad scientists they were, Konopka and Benzer treated their population of flies with a chemical that created mutations in the fly’s DNA, and then they screened through subsequent generations looking for as many Joe Mutant flies as they could find. In 1971 they reported the discovery of three classes. First, there were the insomniacs. The Manic Fruit Flies that would punctuate long periods of movement with short erratic pauses, oblivious to whether there was light or not (B. arrhythmic mutant). Second, there were flies that punched out early for a 19 hour cycle (C. short-period mutant). Finally, there were flies that worked overtime for a 28 hour cycle (D. long-period mutant). These three behaviors turned out to be caused by three different mutations in a single gene, named Period, a gene conserved through evolution all the way up to humans, to Konopka and Benzer, to you and me.

In 2017, the Nobel Prize was jointly awarded to Jeffrey Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Michael Young for their discoveries unraveling the molecular mechanisms of this intrinsic clock. Here’s the gist. In the light, a pair of proteins (named CLOCK and CYCLE) combine to positively stimulate the gene expression of key proteins in our cells. However, among those proteins are our old friend PERIOD and another protein named TIMELESS. In the dark, PERIOD and TIMELESS build up, form a complex, and block the function of the CLOCK+CYCLE protein dimer. This shuts off expression of all those regulated genes, including PERIOD and TIMELESS themselves. A classic negative feedback loop. The trick is, when the sun comes up, light causes the destruction of the PERIOD+TIMELESS protein dimer, which frees up the CLOCK+CYCLE complex to start inducing gene expression all over again. And around we go.

The take-home? Our circadian clocks are highly sensitive to light. Their cycle times, and the expression of all the downstream target genes, are easily coerced out of sync by rogue light pollution. Current research indicates that clock abnormalities like this are linked to sleep and mood disorders, the disruption of metabolic and endocrine activity, pathology of the immune system, and cancer.

.=.=.=.=.=.=.

We packed the car and headed the 877 miles north to the 2nd annual “See The Dark Festival.” The Festival, hosted at the Appalachian Mountain Club’s (AMC) Medawisla Lodge, was in the back of beyond, at the end of miles of gravel logging roads, nestled up along the shore of Second Roach Pond. It’s dark there. Bortle Scale number 1 dark.

In 2021, the AMC’s North Woods properties, spanning some 14,000 square kilometers of wilderness forests, were certified by DarkSky International as the AMC Maine Woods International Dark Sky Park. It took years of meticulous measurement, documentation, and commitment to preservation, education, and access to secure that designation.

The Festival is one of the tangible products of all those efforts. Running for a week, this year boasted a packed schedule of star watching, instruction, astronomy talks, cultural events. Oh! And free beer tastings presented by Allagash Brewing Company.

.=.=.=.=.=.=.

When we finally arrived at Medawisla Lodge the sky was dark all right. Too dark! Dense black clouds blanketed the sky from horizon to horizon, a disappointing continuation of conditions that had persisted for the past three days. There would be no outdoor star gazing this night. But! There was a Plan B, and it was great.

John Laatsch, Director of the Versant Power Astronomy Center and Jordan Planetarium at the University of Maine, gave a presentation on the upcoming 2024 solar eclipse. Definitely a must-see occasion!

After that, John Meader led us through the mid-October sky, indoors, by computer projection. John runs Northern Stars Planetarium, with a mission of educational out-reach, particularly for Maine school systems. Practiced and comfortable entertaining elementary school kids, John’s gift for teaching was perfectly tuned to all the eager old kids assembled this night at Medawisla. We came to rely heavily on his wit, humor, and extensive knowledge over the course of the week.

On another evening, Jenny Ward, Director of Brand Experience at AMC, talked about the history of the Dark Sky Project, all her long night slogs with a light meter chasing Bortles through the woods, the community outreach and partnering, and the ongoing plans for the Dark Sky Park future. You can read an interview with Jenny on these topics and a recent piece she wrote for AMC, “How to Protect the Night Sky.”

One of the treats of the Festival was a performance by “Poetry with Strings Attached”, comprising poets Kristen Lindquist and Paul Corrigan, together with string duo violinist Susan Ramsey and cellist Ruth Fogg. The theme “Natural World through Poetry & Music” played out with Lindquist and Corrigan reading selected poems, alternating with music from Ramsey and Fogg. Impressive and absolutely delightful.

Each of those first couple of nights, I left the talks, left the Lodge building, with a head full of exploding giant stars, bright colored binaries, flying Cygnus, fragments of Lindquist’s “God of Sea Ducks”, and ear-worm bits of Irish melodies. Looking up at the sky on the way to our cabin? Clouds. There would be no star gazing again this night.

.=.=.=.=.=.=.

Physiology woke me up and forced me out of bed. No more denial. I had to pee. The cabin was cozy, but I was going to have to make the short trip across the field to the bath house facilities. I donned a headlamp, stepped out the door, and was immediately hit by a damp mid-night chill. Grumble, grumble. Trudge, trudge.

Then I looked up.

“Good Heavens!! WOW! That is AWESOME!”

The clouds had cleared and the sky was illuminated by the light of a billion stars. The Milky Way was a wild, glowing, Jackson Pollock drip painting strung across the top of the sky. The starlight I gathered, the photons from the Andromeda galaxy, for example, just now tickling the receptors in my eyes, started their journey across space well over 2 million years ago. A gift. Photons never before seen, nor ever to be seen again, by anyone else but me.

.=.=.=.=.=.=.

I hauled my tripod and camera out of the cabin and gingerly worked my way down in the dark towards the dock for a wide open view of the sky. The red headlamp providing weak and begrudging assistance. Jupiter thought this was pretty funny.

I had practiced this. Dry runs to check the remote shutter release, the manual settings, the focus. But the camera you use routinely during the day, becomes a doorstop in the dark. The aperture dial morphed magically into the mode dial and, instead of opening the lens, I switched the camera to Auto mode. The poor thing became confused trying to figure out what it needed to do in order to take a picture deep in a coal mine. The lens has a focus from near to infinity. Infinity seems pretty much out there where the stars live, I reasoned. Just dial the focus out to infinity and that should do it. Well, no. The lens designer and I have a disagreement about the meaning of infinity. At this point, Jupiter pretty much spit his coffee out across the sky.

OK, wise guy. I’ll focus on you.

He snapped to attention, brushed some stardust off his armor, and casually mentioned that he was just passing through.

Finally, with the help of Altair, I captured what mind’s eye had been seeing all along. A star-studded sky over the trees of Medawisla. Hard to breathe. Suddenly, there I was again, peering out the window of the old yellow station wagon, being carried down winding country roads, as Aquilla the Eagle soared high overhead.

.=.=.=.=.=.=.

The following night presented the Festival with a perfectly gorgeous sky. John set up two 8” reflector telescopes: the Celestron, an impressive three-legged sculpture of clockwork, wires, and optics; the Orion, an avantgarde recreation of a cannon from the USS Constitution. John ferried us around the universe with a laser pointer, the actual real universe this time, sending 488 nm photons out to infinity as a gift of his own.

I am convinced that humankind’s first conscious encounter with the stars came about in the middle of the night when one of our primordial ancestors left the cave to relieve themselves.

And looked up.

Whahg!! Dabbnub rut Brodozzlefrackik!!!

[ Holy sh?t!!! That is AWESOME!!! ]

Anyway.

That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.