Chasing a Second Blackout

It was always likely to be cloudy. We knew that going in. According to the climatology odds, we had only a 1-in-3 chance of clear skies for viewing the eclipse. And the Thousand Islands region in early April? Well, if it wasn’t freezing cold and raining, at least it would be cloudy and windy.

The thing is, the weather forecasts beginning the week before had been shockingly great. Sunny, with highs in the mid-50s, was the proclamation. Surely, the weather folks can do accurate 7-day predictions, can’t they? Maybe. But, as the week advanced, the forecast back-tracked a little worse with each update. “Sunny” became “mostly sunny”, which became “partly cloudy”, which digressed to “mostly cloudy”, which was shortened to just “cloudy” to save pixels.

The problem was that the eclipse apparently couldn’t keep up with the prevailing weather pattern. The day before the eclipse had been a terrible tease: a bluebird day, not a cloud in the sky, with a high temperature in the low 60s. Tee shirt and shorts weather, a freak of global warming!

Then the clouds started rolling in from the west early that evening, as if to mock the eclipse, “You snooze, you lose.”

So here we are, midday on April 8, 2024, the day of the eclipse, and the sun is just a distorted smudge behind banks of dark clouds that run from one horizon to the other.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-

I wasn’t that invested. Been there, done that.

Over 50 years ago, when the eclipse of March 7, 1970, raced across the east coast of the US, Sue and I drove from Baltimore to Assateague Island, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, to catch the blackout. Now, in late March 2023, my recollection of that event had atrophied into a sort of “meh.” Sure, it got dark. Must have, no? Maybe the seagulls shut up for thirty seconds; I don’t recall. The only residuals I could summon were related to the human scene: the hippies mesmerized with bongo rhythms, and hucksters proclaiming “The End of the World,” while making pilgrimage over sand dunes. The real-life stereotypes of the 60’s and 70’s cultural landscape. So in late March, 2023, when Sue got excited about another trip to view a solar eclipse, an eclipse still more than a year away, I confess I didn’t feel inclined to dig out the pom poms.

The challenge of staking out a site with the best chance of clear skies didn’t loom large. In fact, any location along the magic “Center of Totality”, within a reasonable driving distance from home, had exactly the same overwhelming probability in favor of invisibility given any random April 8th day in weather history. Therefore, what the heck, we might as well go somewhere interesting, and new to us, where a failed eclipse wouldn’t be The End of the World.

Thus, we settled on The McKinley House B&B in Clayton, New York. Clayton is a small seasonal resort village nestled in the Thousand Islands region, docked right along the southern shore of the St. Lawrence river. This promised several advantages, including the eponymous islands, big old commercial ships chugging past up the channel, and a plethora of interesting harbors, waterfront activity, maritime museums, and history. Plus excellent restaurants.

Although we seemed to catch them by surprise with the Eclipse Thing, the McKinley House graciously accepted our reservation more than a year in advance. They wouldn’t be surprised for very long. And “gracious” turned out to be the appropriate watchword for the McKinley House. Highly recommended.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-

It would be reasonable to imagine that mapping solar eclipses is a skill of prestidigitation only recently acquired by NASA. After all, if you see one eclipse – and you remain steadfastly in the same spot – you are going to need to wait roughly 375 years before another happens to come your way. Who would be keeping track over 375 years? To score a couple of anecdotal events? If your fastest means of travel was by horseback, perhaps a carriage if you were the robber baron CEO of Facetablet, and your communications were transmitted by pony express or human messenger, how would you, or anyone, find out about the eclipse that happened several hundred miles away last year, let alone halfway around the world a century ago?

It turns out, of course, that I am alone in having the memory of an eclipse rhyme with ‘meh’. In times B.C., a total solar eclipse was a very, very bad omen for the ruling Big Cheese Monarch/Emperor. And thus, an eclipse was also a very, very big deal for you, the astronomer, hired by the Big Cheese Monarch to predict them. Correctly predict an eclipse, and the Big Cheese could terrorize the peasants out of more corn and apples. Some small fraction of which might end up in your larder. But miss out on a surprise eclipse, and you likely cashed in your ticket to the far side of the moon. So you kept good records, and hobnobbed with as many other astro-lackies as you could cultivate, as long as they weren’t local threats to your otherwise cush job.

History records that the first successful prediction of a solar eclipse was made by Thales of Miletus in 585 BC. That blackout, over what is now modern-day Turkey, so scared the hell out of the Lydian and Medes armies that they declared a truce and ended their six year war. Some things were, indeed, simpler back then. To be fair, Thales didn’t actually tell us all this. But we have hearsay evidence from Greek history professor Herodotus a century later, and he swears it’s the truth. Thales was probably just winging it.

Edmond Halley was a Newtonian geek. In 1705, using his friend Newton’s mathematical framework, he announced that what were thought to be three separate comets, appearing in 1531, 1607, and 1682, were actually one and the same object. Furthermore, he predicted that this comet would return roughly every 76 years, which it has done faithfully, right on time, through 1981. And counting. Ten years later in 1715, while waiting for his comet to return, Halley published a detailed map predicting both the path and the timing of a total solar eclipse that would traverse London a couple of days later, on April 22, 1715. The map was accurate to within 4 minutes and 20 miles on its northern edge. And that prediction wasn’t for a Big Cheese Monarch. Not for corn and apples. Halley publicized his broadsheet widely to dispel public superstition and ignorance about eclipses, to counter fantasies of “Jewish space lasers” and “Q-anon conspiracies.” Halley wrote of the public:

“They will see that there is nothing in it more than Natural, and nomore than the necessary result of the Motions of the Sun and Moon.”

More Halleys, please.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-

At the atomic level, weather is a crap-shoot.

The clouds got thicker and thinner and then thick again. Through the blocking optical density filters, we could see the outline of the black dragon slowly devouring the pastel red sun, the lines becoming alternately sharper and blurrier in cycles. Brian set up his scope on the lawn next to me. We commiserated over the futility of having calibrated sun exposures the day before when there wasn’t a cloud in the sky. Now the lighting changed so quickly, with the variable cloud cover, that yesterday’s calibrations were useless. It was every F-stop for itself.

All the way up I-81, from Syracuse to Watertown, mobile highway signs had flashed:

But the eclipse was on a tight schedule, dictated by Edmond Halley no doubt, and it was in no mood to be delayed.

Forty minutes before totality.

The open patch of blue sky first appeared far off in the distance, out on the northwest horizon. The clouds were definitely moving slowly southeast. Would the winds bring us that break in the clouds? Would it arrive in time? It wasn’t a big opening; maybe it was bigger than it looked? I exuded faux confidence, and fidgeted optimistically with the camera, but Brian was skeptical. Then he was upbeat while I played the sad trombone.

-=-=-=-=-=-

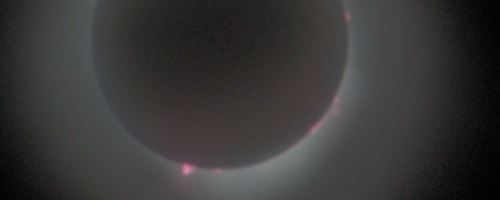

The timing was beyond stagecraft. The sky opened and the moon, in slow motion, slid completely across the face of the sun. It was dark, sure, and noticeably cooler. But the dark wasn’t nighttime dark, it was magical. The glow of the corona a vision of dreams. The boggling concept of three celestial scale objects moving into perfect alignment, temporarily, nothing special for them, was absolutely awesome for us. The complexity was disconcerting. I knew to look for the “diamond ring” as the occluded sun is reduced to its last point source exposure. I knew to look for “Bailey’s Beads, as jubilant photons are still able to sneak through the valleys between mountains on the moon. But who knew of “solar prominences”!

-=-=-=-=-=-=-

For a profession that can conjure up “black holes”, a “Helix Nebula”, and a “Crab Nebula supernova remnant”, you’d think there would be a more dramatic name than “prominence” for the bright red beads exploding from behind the moon during totality. A “solar prominence”. Really? That’s it? That’s the best you can do? “Prominence” is an attribute we apply to our local Commonwealth’s Attorney, not a blazing cauldron of plasma zapping away within a restraining Rorschach mess of magnetic fields 500 light seconds out in space.

A solar prominence (also known as a filament when viewed against the solar disk) is a large, bright feature extending outward from the Sun’s surface. Prominences are anchored to the Sun’s surface in the photosphere, and extend outwards into the Sun’s hot outer atmosphere, called the corona. A prominence forms over timescales of about a day, and stable prominences may persist in the corona for several months, looping hundreds of thousands of miles into space. Scientists are still researching how and why prominences are formed.

The red-glowing looped material is plasma, a hot gas comprised of electrically charged hydrogen and helium. The prominence plasma flows along a tangled and twisted structure of magnetic fields generated by the sun’s internal dynamo. An erupting prominence occurs when such a structure becomes unstable and bursts outward, releasing the plasma.

I sought a little context for the prominences photobombing my images. The diameter of the moon spans roughly 0.5 degrees and it is about 260 pixels wide in the raw images. The long dimension of the major prominence (located at 6:30 on the dial in the image above) is about 8 pixels. Given image diffraction and distortions, let’s peg that dimension at closer to 4 pixels in a perfect image. This defines an angle of 0.0077 degrees for the isosceles triangle projecting out 93 million miles to our prominence magnetized to the refrigerator door of the sun. A little eighth grade trig suggests that this heroic prominence is thus a blasting loop of plasma extending roughly 111,600 miles out from the surface of the sun. The earth, for reference, is 7,926 miles in diameter; we need 14 of them stacked pole to pole to bridge the height of our prominence.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-

So why “meh” over the 1970 eclipse? What could possibly have been wrong with me? This Thousand Island eclipse was the anti-meh, the “HEM”, capital “meh” spelled backwards. It defied words, a Word beyond grasp, a reality to which this paltry essay can’t come within 93 million miles. So what was with that 1970 experience? I couldn’t shake the uncomfortable feeling that I was wrong about something. I was. The answer turns out to be found in the Halley-esk map for the path of totality traced by the 1970 eclipse. Viewing from Assateague Island? We were some 50 miles just outside the shadow of totality. We had witnessed a partial eclipse. There is no comparison.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-

The clouds soon closed back in, blotting out our view of the sun as it escaped from the shade thrown by a disinterested moon. The day quickly reverted to a normal hazy April in the Thousand Islands. The eclipse was objectively as Halley wrote: “no more than the necessary result of the Motions of the Sun and Moon.” A celestial event with “nothing in it more than Natural.”

Still.